Dartmouth College Fund: Financial Aid

In uncertain times, one thing is certain: Dartmouth stands by our students. Give now to help students in this moment.

Geeta Anand talks about her undergraduate activism, how Dartmouth prepared her to be an award-winning reporter, and the state of journalism today

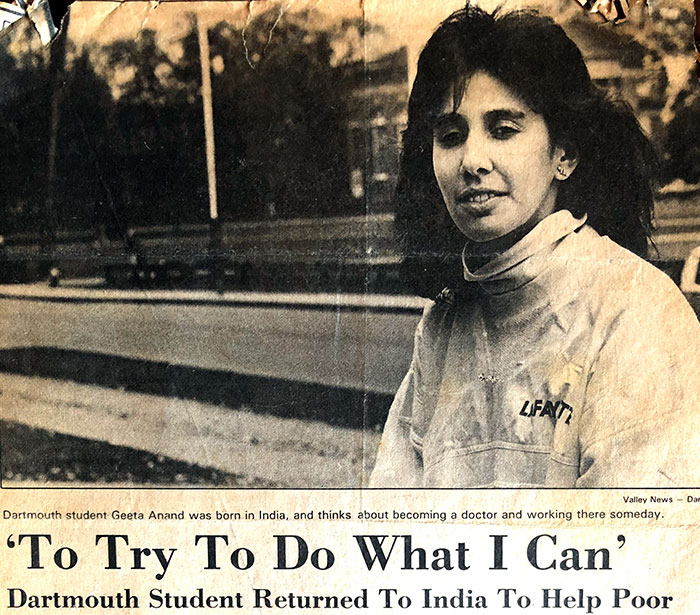

Geeta Anand ’89 P’22 is a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who is now the dean of the University of California at Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. Born in India, Geeta started her journalism career immediately after graduating from Dartmouth at a free weekly newspaper on Cape Cod and then moved to a small daily in Vermont. She later worked at The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times. She shared the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory journalism at the WSJ for a series of articles on corporate corruption. She was later a correspondent for the WSJ and New York Times in India. While in Mumbai, her husband, Greg Kroitzsh ’87 P’22, opened the city’s first microbrewery. Geeta authored the book The Cure, later turned into the movie Extraordinary Measures, based on stories she wrote as a biotech reporter. She is a member of the Dickey Foundation Board of Visitors and a steadfast supporter of the Dartmouth College Fund, in gratitude for the scholarships she received as an undergraduate.

I had a phenomenal experience at Dartmouth, but there were challenges. I was president of the International Students Association during the time of the anti-apartheid movement on campus. There were divisions within the association over whether we should be more of a political organization or focus on supporting students. Although I was involved in the anti-apartheid movement, my view was that international students needed so much support. In those days at Dartmouth, it was hard for international students to feel a sense of belonging because there were so few of us.

Trying to bridge that division within the association taught me how to reach out and understand others. There was a lot of aggressive behavior on campus at that time. I was part of the group of students who built a shanty town on the Green to protest the College’s investment in companies doing business in South Africa, and some other students would come out at night to bash it to pieces. But the experience of actually getting into conversations with people who thought differently helped me see the good in people with different political points of view, and how to even build coalitions with them.

All of this led me to take leadership positions in advocating for change. Those experiences taught me to stand up for what I believed in. And then there were amazing professors who took part in the divestment movement and other activities. I found great mentors who were very supportive.

I left Dartmouth believing in political activism and believing that it’s possible to change institutions. Now I see students at Berkeley demanding change to address systemic racism at our school, and what they’re doing excites me.

I wrote a few articles for The Dartmouth, but it was the academics that prepared me for my career. I was a history major, and through my history classes I learned that I loved writing. And the liberal arts experience—taking courses in economics, chemistry, acting, music—expanded my understanding of context and gave me the confidence to believe there wasn’t anything I couldn’t figure out. When I was asked to do the biotech beat at The Wall Street Journal, I wasn’t scared for a second that I wouldn’t be able to understand it. I knew how to ask questions and analyze information.

I shared a Pulitzer at The Wall Street Journal for explanatory reporting for a series of articles exploring corporate corruption. I wrote two of the stories, and one focused on Sam Waksal, CEO of a company called ImClone—one of the big stories that year was how he and Martha Stewart had allegedly engaged in insider trading. As a reporter, I liked to think the series had impact. Sam Waksal did get sentenced to jail for seven years. More broadly, I’d like to think it changed how people behave. But change is incremental, and sometimes people go back to their bad behavior.

Many of our students are really worried about careers in journalism because the market is shrinking. They’re also challenging some of the basic premises of journalism and, among other things, challenging us to think differently about what objectivity means. I love being able to engage with them in these discussions.

Journalism has never been more important than it is now, although these are difficult times for the profession. Journalism is under attack from our national leaders, and hundreds of newspapers have closed in recent years, which is devastating because local papers are vital to democracy.

It’s really worrisome that there is so much disinformation in the world that many people no longer believe there are actual facts, which are the basis for discussion. If you can’t even agree on a set of facts, how do you as a country have a dialogue about anything? We’re doing excellent, excellent journalism in America, but half of the population isn’t reading our stories anymore. They’re reading skewed news stories that aren’t based on facts but are spread across the internet by social media sites using algorithms to promote the most controversial exchanges. This is the biggest threat to democracy, peace, and a sustainable world, more than any war. Journalists must challenge our government to address this problem immediately.

At the same time, I see a lot of hope. Many people across the country are realizing just how important journalism is to their communities. And there are new and different types of communities out there where information is gathered and shared completely digitally.

I emphasize to our students that storytelling is still important and learning the fundamentals of writing and reporting are essential even if you’re using other models of storytelling. Journalism is relevant and alive.