A Renovated and Expanded Hood Museum Opens Its Doors

Artist Mateo Romero ’89 talks about the struggle and magic of creating art

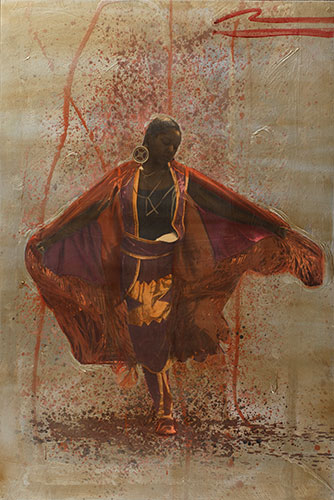

Mateo Romero ’89 is an award-winning Pueblo painter. Hailing from a family of Southern Keresan Cochiti artists, Romero studied painting and art history at Dartmouth under Ben Frank Moss and Varujan Boghosian. His internationally exhibited artwork boasts bold colors, thick layers, and mixed surfaces that channel the vibrancy and richness of Southwest Native culture. He lives in Pojoaque Pueblo, New Mexico, and paints at his studio in nearby Santa Fe.

I’m the most challenged and the most tense—but also the most joyful, and the most connected to the world—when I paint.

I have a beautiful studio. When I’m here at night working on a big painting by myself, there’s a feeling of magic. I have an old vinyl collection and I put music on. The light’s just right. The air is really crisp in the desert and the temperature drops quickly. I actually sometimes feel like I’m not even there, like at the end of the night it’s done. It just happened. It wasn’t really a conscious thing; there’s an intuitive chemistry in my body. I’ll place a certain color and bring a quality to the surface, and I’ll think, “That’s just how I wanted it to be, and I didn’t even know it. It’s perfect.” Those moments are such elation, an out-of-body experience with emotions carrying you through. It is magical to be able to participate in the world in that way.

It hasn’t been easy to get to this point. When I was at Dartmouth, an instructor told me: “It takes five years to learn how to draw, and five more to learn how to use color, and if you do it both simultaneously, you can really focus and nail this thing in five years—but it takes absolute concentration.” It’s like being an athlete. It takes work every day.

It can be a struggle, because most artists aren’t supported in our society. Some of the best artists I’ve met—amazing artists with soulful, profound, personal, well-built stuff—were in grad school, working as waiters and struggling to sell one painting a year, and they couldn't sustain it because there wasn’t financial support.

There were times I failed, I wasn’t embraced, or I just didn’t get it right. Regardless, I chose to completely commit to the studio art process. It was my vision for how I wanted to interact with the world. It was a sketchy vision with no economic certainty, but my training at Dartmouth gave me the ability to embrace my dream. My genuine intellectual curiosity was nurtured at Dartmouth, and as a liberal arts college, it helped me develop a critical thought process that I used to go after what I wanted to do without reservation. I feel blessed that I found this studio art movement, that people responded to my work, and I’m fortunate enough to have collectors and museums now supporting it.

I don’t want my art to be totally personal and idiosyncratic. As an artist you have to create a vision of your own truth—and it has to be something that’s authentic to you. But it also has to connect with other people.

I’m an Indian artist making Indian art. I was born into it. My father was a Cochiti Pueblo painter. My grandmother is a famous Cochiti polychrome pottery artist. So, I came from a lineage of talented artists who were very culturally framed. Everything about my life—including going to the Native American Program at Dartmouth—has been colored by being Native.

If someone were to label me a leader in the contemporary Native art movement, I wouldn’t stop them—but I don’t say that about myself. I struggle with the idea of being a leader, because the idea of an individual leader is not really a Pueblo idea. In Europe and America, there’s this idea that the artist is individual, and the artist has a license to create—even if that includes bad behavior. But in Pueblo culture they say: “It’s group think. It’s group talk.” It’s a more socialistic experience. Leadership is being a part of a group and serving a group.