"We are Finally Talking About Racism as a Problem Worth Solving"

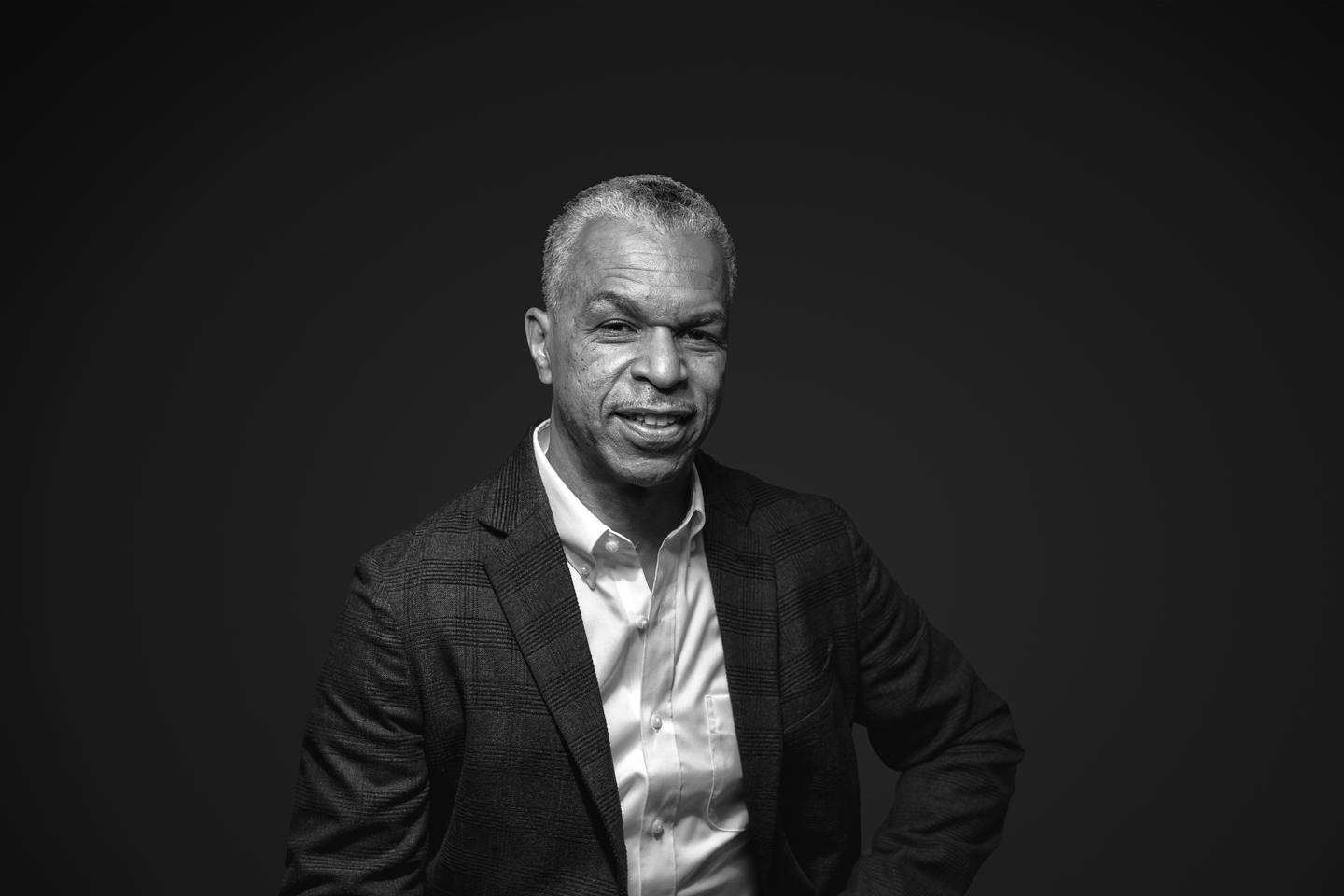

Trustee Emeritus John Rich ’80 H’07 talks about his journey from Dartmouth to addressing the blight of racial trauma.

Trustee Emeritus John Rich ’80 H’07 came to Dartmouth at the suggestion of Edward Wood ’53, an ophthalmologist and family friend. After graduating with an AB in English, John received his medical degree from Duke, followed by a master’s in public health from Harvard. Working at Boston City Hospital, he was struck by the steady stream of injured young Black men arriving in the emergency room and encountered the assumption of health care professionals that these victims of violence were drug dealers or gang members responsible for their injuries. That experience shaped the mission central to his career: creating better primary care for young men of color and giving them a voice and a role in the health care system.

Today, John is a professor of health management and policy at the Drexel University Dornsife School of Public Health. He cofounded and directs the Drexel Center for Nonviolence and Social Justice, a multidisciplinary initiative focused on reducing violence and trauma and improving physical and mental health. John has received multiple honors for his service to public health, including an honorary doctorate from Dartmouth, the National Medical Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

A different sensibility

I was premed at Dartmouth, but I discovered that I didn’t have to be a science major to go to medical school. That was great because faculty like Bill Cook, an amazing African American writer and professor, had gotten me interested in English. Deciding to be an English major was an awesome choice for me. It introduced me to professors from so many perspectives, all of whom were brilliant.

Dartmouth at the time wasn’t a place where you could talk about race comfortably. There was general sense that the inequalities of life were just the way the world works—a social Darwinism idea that Black people were disadvantaged. The notion of racism as a transfer of opportunity, that it doesn’t just hurt Black people but advantages white people, was not a conversation we could have then.

Having served on the Board of Trustees recently, I believe today’s students arrive with a different sensibility. It’s not that all of Dartmouth has changed. Rather, most students and faculty now are more advanced in terms of how they can have those conversations.

I went to the Duke School of Medicine immediately after Dartmouth and my residency was at Mass General Hospital in Boston. Near the end of my residency, I went across town and visited Boston City Hospital. Something about that place got hold of me. I realized that this was how I wanted to spend my career—caring for people where I didn’t have to know whether they had insurance. I just knew I was there to care for these people.

Systems to prevent illness and injury

This was 1989. We were in the midst of the HIV epidemic, which was disproportionately impacting young people of color, and there was a terrible violence epidemic. With HIV, we basically were treating infections and shepherding people to the best and most comfortable death that we could. With violence we were, again, just treating people. That of course is important, but I began to think about how we could create systems of care that emphasize prevention.

One of the first things I did was to establish the Young Men’s Health Clinic to provide primary care for young men of all colors in their 20s and 30s. If young men disappear from the health care system between pediatric care in their teens and primary care as young adults, and then they reappear somewhere around age 50 with no treatment of problems like hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, we’re basically playing catch-up.

As I began talking with my peers about better primary care for young Black men, someone would immediately say, “Oh, yeah, violence prevention.” There was a clear dichotomy: primary care for us, violence prevention for them. That begins to characterize the kind of dehumanizing position we find ourselves in. Those of us in a position of privilege often think about poor people and people of color as needing and deserving something different, something less. That’s a root cause of the health inequities that we see.

As I wrote in my book Wrong Place, Wrong Time, early on in my career I realized that I too held some of those subtle biases. There was a sense young Black men don’t just get shot; they get themselves shot. This assignment of blame didn’t take into account any of the toxic stress and social conditions or social determinants of health.

“There was a sense young Black men don’t just get shot; they get themselves shot.”

The power of stories

I started talking with young people recovering from violence about their experiences, and I’ve conducted hundreds of interviews over the years. Sitting with these young people, giving them the time to tell their stories, I began to hear stories of trauma caused by violence, whether inflicted by others in the community or by the police, and the pain of racism and racial trauma.

I recognized their symptoms as being very much like those of post-traumatic stress, except for many of these young people there is no “post.” The trauma is continuous. And the weight of this persistent trauma closes off your sense of future.

Here is what these young people helped me to understand: If we believe violence is senseless, then we think there’s very little that we can do. However, if we understand the root causes of violence—that it has to do with structural racism, a fundamental lack of opportunity, racial trauma, and traumatic stress—then we can do something. We can create opportunities for young people to heal while we also work to dismantle systemic racism.

How had Dartmouth prepared me for this? In at least two ways. The first was the humanity of professors like Bill Cook, who helped me understand issues of race and racism. And he, along with others such as Professors James Cox and Donald Pease, cultivated my love of stories and helped me understand the power of narrative.

I took this with me into medicine. I was trained in quantitative research methods at Harvard. When I got to Boston City, I met health care folks who had come out of anthropology and philosophy. They schooled me in qualitative methods and narrative research. Sometimes, I was hearing people’s stories as a doctor working in the clinic. At other times, I was working as a researcher seeking to understand their experiences in their own words and analyzing their stories.

I still do that work with young people who’ve come through a program called Healing Hurt People, which my partner and I cofounded. It’s hospital-based intervention for young people who’ve been victims of violence and want to heal their trauma to prevent re-injury. In addition to using measures such as PTSD scales, we ask open-ended questions to understand their unique life experiences not captured by these instruments. And we actively engage in helping young people to tell their own stories through digital media.

“If we believe violence is senseless, then we think there’s very little that we can do.”

Change at Dartmouth and beyond

I sit on an external review committee for Dartmouth’s inclusive excellence efforts. There’s good work taking place at Dartmouth, but there’s always more we can do.

While young people in America today have been part of a broader societal conversation to name racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of hate, much of the fundamental lack of opportunity persists. Leading educational institutions such as Dartmouth can help effect positive change. We shouldn’t be sheepish about aspiring to do that. We need to be bold.

“Leading educational institutions such as Dartmouth can help effect positive change.”