“OPPORTUNITY ISN’T ENOUGH. YOU HAVE TO WALK THROUGH THE DOOR.”

Robert Higgins ’81, president of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, talks about the teamwork skills he learned at Dartmouth.

Heart and lung transplant surgeon Robert Higgins ’81 is the first African American to serve as president of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital. His appointment to lead the internationally recognized academic medical center is the latest in a series of career firsts for Higgins that includes surgeon-in-chief at Johns Hopkins and surgeon-in-chief and director of the Wexner Medical Center Comprehensive Transplant Center at Ohio State University.

After his father died in an auto accident in South Carolina, five-year-old Bob Higgins, his two brothers, and his mother moved to the Albany area to live with his maternal grandparents. Two years later, the extended family moved into an all-white suburban neighborhood, only to have their new home destroyed within 24 hours by fire in what investigators termed a “suspicious circumstance.” Despite these challenges, Higgins attended a military academy at great family expense, graduating as an academic star, three-sport athlete, and major of the cadet battalion in his senior year before coming to Dartmouth (early decision; he didn’t apply to another college). He received his medical degree from Yale, followed by eight years of training in general and cardiothoracic surgery, specializing in heart and lung transplantation, including service at Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, England, one of the world’s premier heart and lung transplant centers. He and his wife Molly have three children pursuing careers in medicine, finance, and law. Their oldest son, John, a member of the Class of 2014, is an orthopedic surgeon in training.

What set you on the path to success?

I was fortunate to have a strong family network that created expectations for us, as young African American men in modest economic circumstances. My mom was a single parent. She worked several jobs and created opportunities for us to get the scholastic preparation we needed to succeed, and she kept us out of trouble by fully deploying us in a rigorous academic environment.

Between your father’s death and losing your home to likely arson, you must have felt a lot of anger and bitterness.

We were taught that we should not be bitter, but that we should use adversity to instill the resolve to overcome prejudice and discrimination in our lives. That was the message. Don’t get mad; get even by your success.

Did you know that you wanted to be a physician at an early age?

My dad was an African American physician in the segregated South in the early ’60s. We had a perception that he didn’t have the chance to complete his work as a physician. The sense that he had unfinished business instilled that desire in me.

What stands out from your time at Dartmouth?

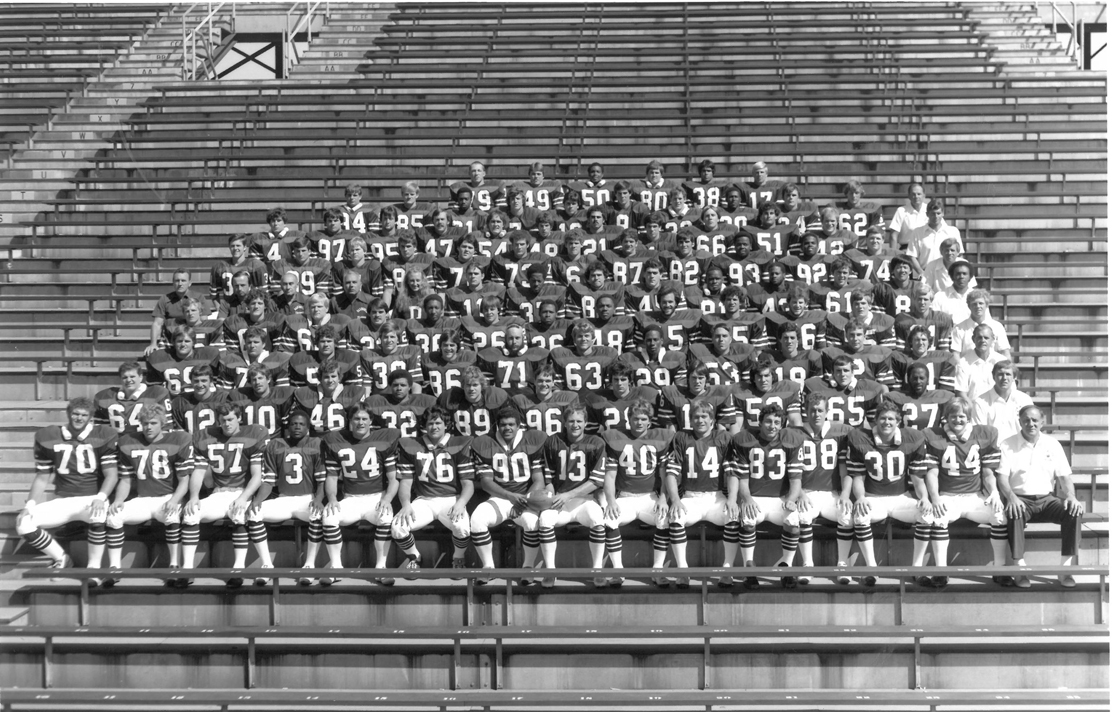

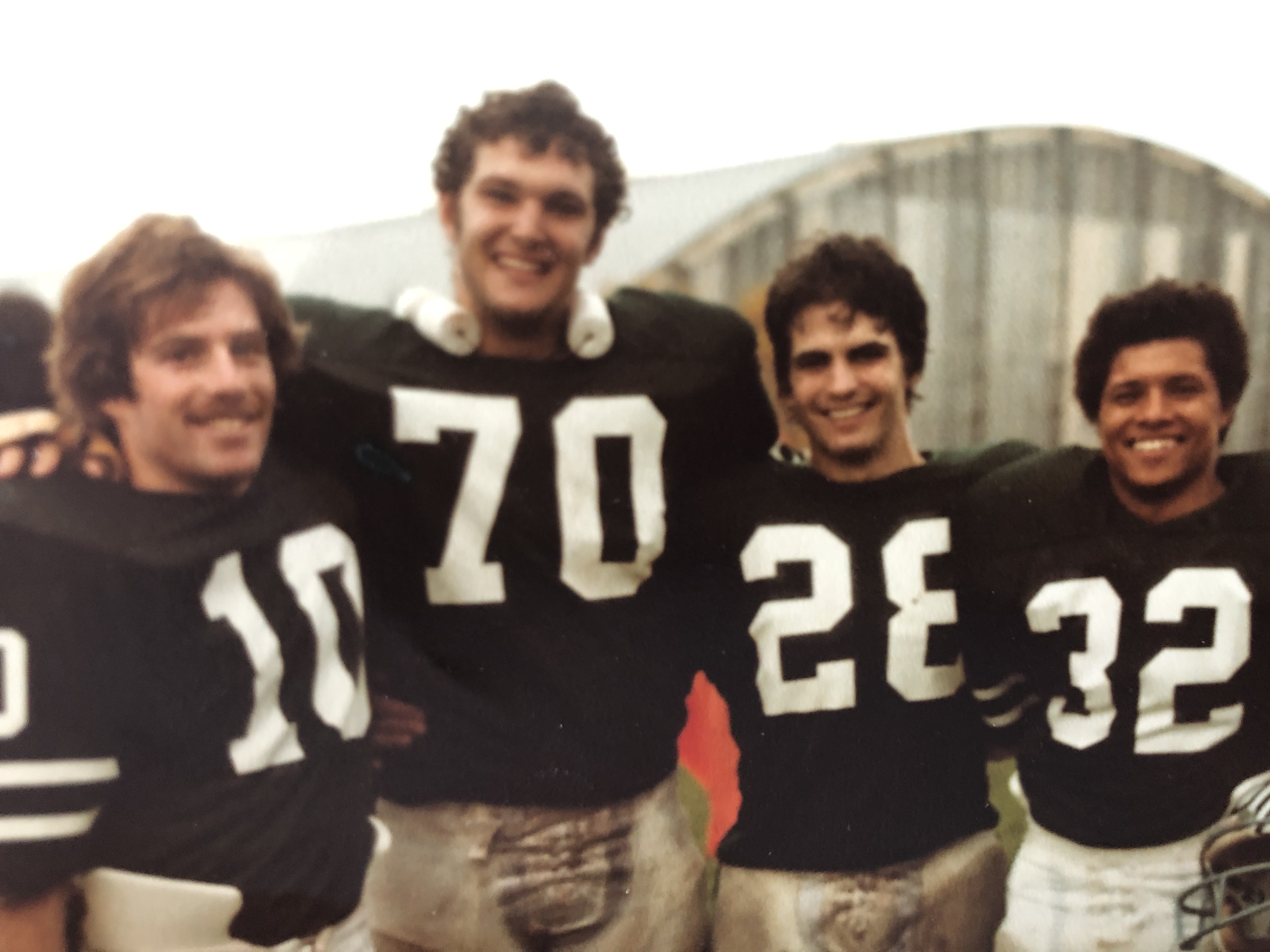

I was not particularly disciplined initially. But it became clear that if I wanted to pursue my aspirations to be a physician, to follow in my father’s footsteps, that I needed to focus. Organic chemistry during my sophomore summer was a breakthrough moment. Coincidentally, I had a knee injury that reduced my playing time on the football team. I was a role player on the practice squad but being part of a team was still important. I was also the manager for the hockey team as a work-study job in the winter and I developed great friendships and a network with classmates like Bob Gaudet. It helped me financially and it was a great opportunity to hang out with some fun guys.

Did Dartmouth provide important leadership experiences?

My professional reputation has developed as a program- and team-builder, someone who can solve problems through collective experience and insight. I know the team sports analogies are often overplayed. But in building teams of exceptional medical professionals, like open-heart surgery and transplant teams, the ability to have a common vision, create a game plan, execute it, and then have a great outcome is essential. I’ve done over 400 transplant procedures in my life and thousands of open-heart operations, but also built successful teams of distinction at places like Henry Ford Hospital, Ohio State, and Johns Hopkins.

At the Brigham, my responsibility is to lead 22,000 employees who are among the best in the world and help them to be even more extraordinary than they already are. That translates well to my experiences at Dartmouth, where I was a member of a team and contributed in valuable ways.

What drew you to be a transplant surgeon?

I loved immunology in medical school, but beyond the technical aspect of exchanging organs, I’m deeply touched by the act of organ donation. These organs come from families who’ve experienced a devastating loss and they have the courage to donate organs to others they don’t know. As the transplant team leader, I feel a responsibility to make sure the donor’s gift is honored by doing the very best we possibly can to extend the life of every recipient.

After training in Cambridge, you went to Detroit. What stands out from your time there?

As a person of color, to serve an inner-city urban hospital with a clinical and academic need was a great opportunity. I learned that communities of color were not necessarily receiving the same level of care that others were getting. Since that time, providing care to the underserved communities has been a priority of my career.

Do individuals of color face particular challenges inside the medical profession?

The number of persons of color in the medical field, particularly my discipline, is relatively small, which reflects on the whole educational paradigm. Elementary and high schools serving communities of color tend not to have the same resources. If you look at kids who are developing essential life skills, like reading, writing, and math, first and second graders in these schools are already falling behind children in better-resourced educational environments. We need to do more at every level of education. And in addition to colleges offering programs like Dartmouth’s E.E. Just Program, which allow students to demonstrate their science proclivity, we need to make sure all students have role models, mentors, and sponsors, as I did.

How do we address this?

The pandemic has clearly highlighted many health and educational disparities in our society. It also has provided us with an opportunity to recognize the societal gaps and to develop strategic plans and intentional efforts to close those gaps. We need a cadre of folks who will pursue the mission of bringing more students of color into the medical profession through mentorship programs and sponsorships—and many of those students will go back and work in communities that historically have been underserved. Creating this platform for change won’t happen tomorrow. It’s going to take many years. It’s also clear that health equity and justice will only be served when those who are not affected are as outraged and concerned as those who are affected. Making that happen is going to take some real energy.

Even then, opportunity isn’t enough. Those fortunate to have an opportunity, as I have, need to walk through the door, be successful, and earn the respect of the people around them. It’s a meritocracy. I’m sometimes hesitant to say that, because if I were a white man, I don’t think anyone would question whether I was qualified or if I’d earned the role of president of Brigham and Women’s. No one would ask, “Does he have the chops to do the job?”

With the career you’ve had, you still need to prove yourself?

Many days that’s true. But I love that challenge. I’m here to prove that I can surpass other people’s expectations. I’m candid about this: We must be direct and honest about this if we’re going to change the perceptions of those who would see my appointment as a politically expedient, contemporary phenomenon.

What would you say to people who characterize your appointment that way?

I’d say here’s Bob Higgins, a regular guy who had some hard knocks growing up and also many breaks, great support, and opportunities. And now, because of his performance, he’s been fortunate to be selected for one of the best opportunities in academic medicine. And I think my track record speaks for that, irrespective of race or ethnicity.

Do you expect your son will face the same challenges in his medical career?

I expect that he will have some of these issues in several ways. He will also have to prove himself as a person of color above and beyond what everybody else has to do. But if he works hard and performs well—serving his patients, profession, and community—he will be successful. The more of us who challenge the paradigm and succeed, the greater the opportunity for everybody else.

It doesn’t sound like you’re going to slow down anytime soon.

No. I appreciate the opportunity and challenge and have a bit more to do.