“Don’t dodge the tough problems. Run towards them and encourage those around you to do likewise.”

Henry M. Paulson Jr. ’68 H’07, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury during the financial collapse of 2008, shares the leadership lessons he's learned at Dartmouth and since.

Henry M. Paulson Jr. ’68 H’07, served as the 74th secretary of the treasury, from July 2006 to January 2009, and led the nation’s response to the financial crisis of 2008. Prior to joining the administration of President George W. Bush, he had a 32-year career at Goldman Sachs, capped by serving as chairman and CEO. Today, he chairs the Paulson Institute, which he describes as “a think-and-do tank” that seeks to foster a healthy, productive U.S.-China relationship. He co-chairs the Aspen Institute’s Economic Strategy Group and, as a lifelong conservationist, he has chaired the Nature Conservancy Board of Directors.

What skills are essential for leaders, and how did Dartmouth prepare you to be a leader?

You can’t lead until you’re actually good at something. Too often, young people make the mistake of saying “I want to lead” before they’ve proved their mettle. Competence matters. The very best leaders are skilled in at least one profession or area.

And, importantly, they have a number of essential traits. They have intellectual curiosity. They play to their strengths, have the humility and self-awareness to understand their weaknesses, and surround themselves with people who complement their strengths and compensate for their weaknesses. They don’t dodge the tough problems or pretend they don’t exist—they run to them. They are problem-solvers who define their jobs expansively.

Dartmouth naturally provides many opportunities for students to develop these traits. I’ll give one small example from my experience. I arrived at Dartmouth a poor public speaker who was nervous in front of a group. I knew this was a shortcoming I needed to overcome. Herb James coached the Dartmouth national champion debate team, and also taught a public speaking course which was available for anyone who wanted to sign up. (What a gift!) So, I enrolled in Herb’s course, and this made a big difference in boosting my confidence and speaking ability, which, incidentally, will never be my strong point! That experience illustrates three points: the rich opportunities Dartmouth offers its students, the importance of knowing your deficiencies, and running toward the hard problems.

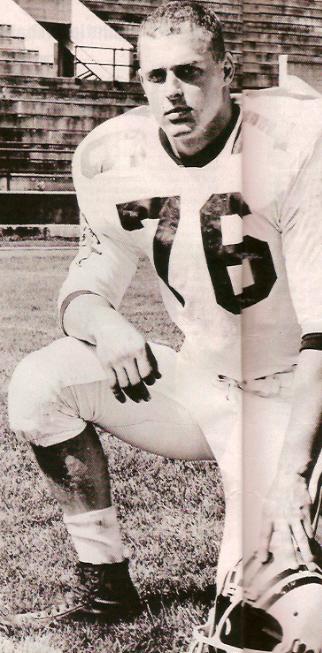

You were an All-East, All-Ivy football player and you later endowed the head football coaching position in honor of Bob Blackman. Can you reflect on how athletics helped prepare you for life?

I was incredibly fortunate to have played at Dartmouth while Bob Blackman was coaching. He was a brilliant coach, truly best in class. I saw how hard he drove himself, and how he set a very high standard of excellence for himself and his players. The football team had a higher GPA than the student body overall. And under his leadership, we became Ivy Champions and won the Lambert Trophy for best team in the East.

I’ve always believed that real happiness comes from working hard, and often working with others, to achieve a goal. That’s ultimately what football gave me. Through team sports, you learn the importance of working as a team—an essential skill for life and for leadership. And, as an undersized and overachieving lineman, I learned how to do the dirty work outside of the limelight—another useful life lesson. Peacocks seldom make good leaders.

I’ve always believed that real happiness comes from working hard, and often working with others, to achieve a goal. That’s ultimately what football gave me.

You spearheaded the U.S. response to the 2008 financial crisis. What did you learn from that experience about crisis leadership and decision-making?

During a crisis, leaders should urge calm, but there must be a healthy balance between conveying calm and being frank about troubling facts. Maintaining this balance is particularly difficult during a financial panic when the facts and our understanding of them are constantly changing. People and financial markets want unattainable certainty, which adds to fear and volatility. Ultimately, actions are more important than words, and my primary priority in 2008 was financial stability.

In a crisis, leaders can never gather all the facts before they need to act. If they wait too long, they’ll find themselves looking at the accident in the rearview mirror. Big, ugly problems don’t have perfect solutions. So, leaders can be forced to choose between not acting, which can be disastrous, or opting for an imperfect solution, made with inadequate information. An imperfect plan usually beats no plan. But this is critically important—when the facts evolve or judgments prove wrong, good leaders are prepared to say, “we made a mistake” and change course.

Dartmouth alumni sometimes talk about moments when something just clicked, such as a class that brought their future career into focus. Did you have a moment like that?

I still remember the lively debates about ideas and literature we would have in Professor Hart’s English class. Or the lessons I learned about policymaking and constitutional law in Government 39, taught by Professor Starzinger. And the great privilege I had learning from Professor Sears, who wrote some of the seminal textbooks in physics.

I was an English major, so the experience of writing my senior thesis sticks out—reconstructing the history of Captain Cook’s third voyage to Hawaii, reading old journals from Jon Ledyard, who went to Dartmouth in the 1770s, and writing a comprehensive paper. The value of doing this wasn’t learning about how and why Captain Cook was killed, per se, but about learning how to think. I learned the difference between good and bad evidence. I learned how to think critically and argue effectively.

From my vantage point, this type of education—a rigorous liberal arts education—is the most valuable. Over the course of my career, I’ve hired people from the top educational institutions all over the world. The very best all-around thinkers and leaders often have a broad liberal arts education from American colleges and universities. I liked to hire English majors.

You’ve spoken about environmental degradation and our nation’s relationship with China as being two issues potentially far more dire than the 2008 financial crisis. What sort of leadership is needed for humankind to address these two massive challenges?

These are both incredibly complex, long-term challenges. They can be daunting—almost to the point of despair—and one person can only move the needle so much. But I wouldn’t be working on China and climate if I wasn’t an optimist, and I believe that leadership can and does make a difference.

For better or worse, America’s climate policy and China strategy are deeply intertwined. If we want a future that avoids the worst climate outcomes and preserves our fragile global ecosystems, we need China to solve its massive environmental problems at home and adopt better practices abroad. And climate policy is one of the important areas where the U.S. and China share common goals and can find ways to work together. We need leaders in both countries to work out a framework for where we will compete and where we will cooperate, and how we will avoid conflict. This will be essential if we are to maintain peace, avoid debilitating competition, and make progress on areas of mutual interest like climate change and denuclearization. If not, the world will be a very dangerous place.

Can you cite some leaders, current or from history, who are inspirational to you?

Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln top my list. Hamilton, as America’s first treasury secretary, was the consummate example of a thinker and doer. He put in place the framework for our modern economy, for the banking and credit system that we all rely on. He did much to support George Washington, win the Revolutionary War, and successfully advocate for the principles at the heart of our democracy. Lincoln is also a hero of mine. During a moment of existential crisis, he saved our nation and redefined its meaning in the process, ending the scourge of slavery. He knew how to work with a team of rivals and forge compromise.

Looking at modern-day figures, I’d point to my old boss, President George W. Bush. One of the best ways to judge the character of a person is to see how they act and respond to situations when things aren’t going their way or when you’re in crisis. He was always willing to do what was right even if it was against his immediate interest. The night of his farewell speech, I had to call him to tell him we needed to do another bailout. Instead of asking us to delay so he could have his moment, he said to go forward and do what we needed to do. I will always have great respect for him.